New Building of the Natural History Museum – Competition

Year of design

Gross floor area

Lead architect

Project architect

Architects

Parametric design

Competition organiser

Visualisation

Gábor Domokos is a Hungarian architect, applied mathematician, university professor, and full member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Together with Péter Várkonyi, he created the convex body later named the “Gömböc,” the first known homogeneous object with only two equilibrium points — one stable and one unstable. In 2024, Domokos, in collaboration with Ákos G. Horváth, Krisztina Regős, and Alain Goriely, proved the existence of a new universal class of shapes, the soft cells, which fill space without gaps or sharp vertices. The inspiration came from the internal chambers of the nautilus shell, which fill the outer structure without corners. Starting from the geometry of the cube, they managed to bend its edges in such a way that not only did the vertices disappear, but the resulting shape also remained space-filling. This led to the creation of the first space-filling cell without vertices.

In joint work with the University of Oxford, they discovered that the geometry of the nautilus chambers is indeed soft. It was later found that, like the nautilus, several now-extinct species also possessed internal chambers without vertices. In nature, soft planar tessellations appear in natural patterns such as the geometry of river deltas, cross-sections of smooth muscle cells, sections of seashells, and the stripes of zebras.

(based on: Wikipedia, Oxford Academic)

The soft cells discovered by the world-renowned Hungarian scientist and his colleagues are ubiquitous in nature as organic basic elements capable of completely filling space. Their existence is both real and transcendent, mathematically proven, yet also tangible. These are structures that, beyond theory, can be used as exciting spatial forms while also offering an experience of connection to nature. Their origin is fundamentally organic, while their scientific description requires a highly developed mathematical and geometrical apparatus. They unite several scientific disciplines, including biology, microbiology, mathematics, geometry, physics, and chemistry.

As an allegory, the soft cell is capable of visually representing the synthesis of the natural sciences.

An iconic example of this class of shapes is the (f2) cell derived from the truncated octahedron — the only known soft cell that preserves the full symmetry of its original polyhedron.

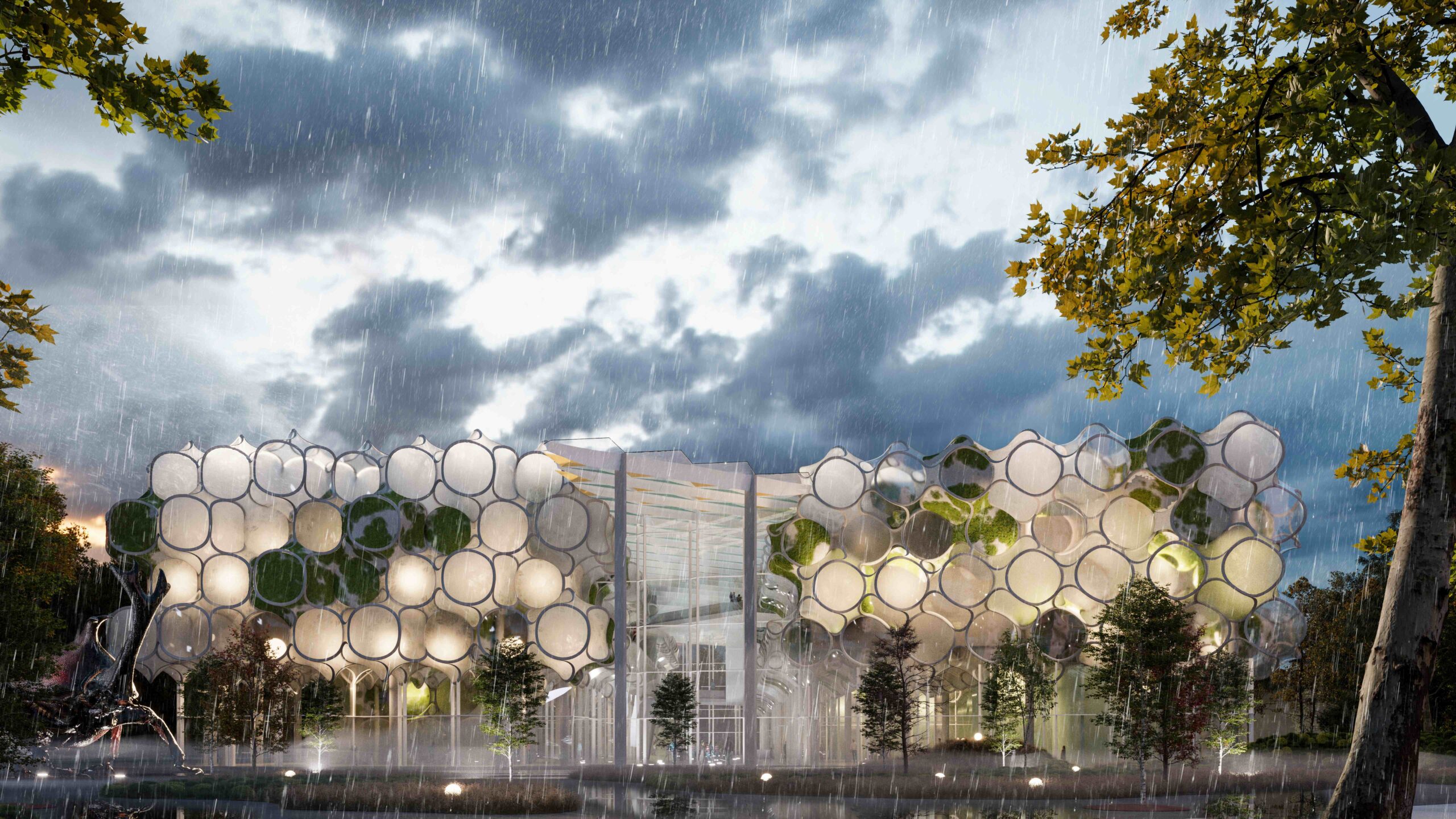

For this reason, the basic building unit of our museum is the (f2) soft cell discovered by Domokos and his colleagues.

Throughout history, architecture has sought to respond in various ways to humanity’s attraction to nature. Most often, this has been done by incorporating natural forms or specific natural elements — sometimes in a narrative manner — to make built spaces appealing to the “biophilic” individual. The integration of plants and organic forms into artificial spaces is a well-established practice.

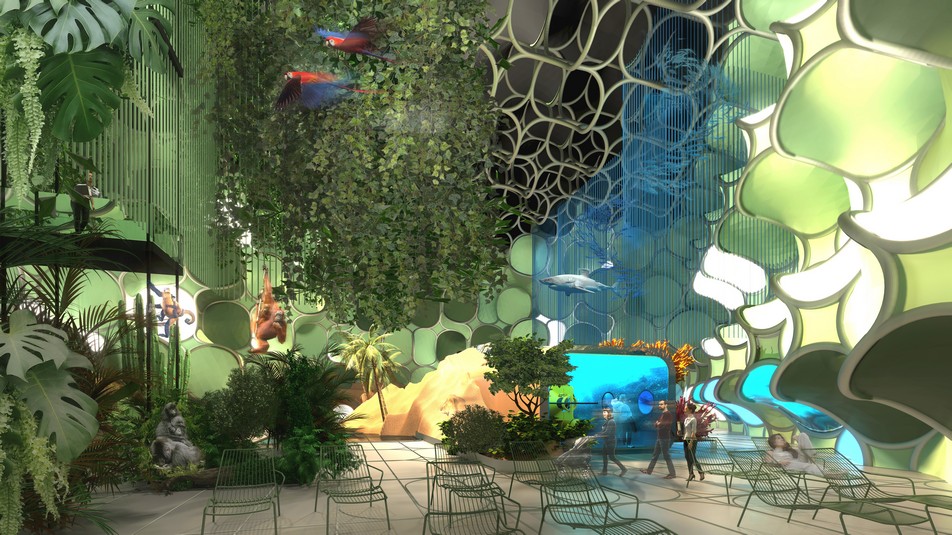

We believe that a nature-inspired spatial logic not based purely on empirical experience can evoke the same mental effect — the pleasant sense of self-definition as part of the “greater whole.” A space constructed from enlarged soft cell elements creates the illusion of looking into and moving within the microscopic structures of nature, offering not only a mental but also a physically nature-connected experience for those moving through it.

The 21st-century museum, beyond being a place for leisure and social activity, is also a venue for ideas of exploration and understanding. For this reason, our building’s design principle is not the tried-and-true importation of familiar, concrete natural forms, but rather the conscious attention to the invisible interconnections of things.

We aim to present the intrinsically intriguing structures of the soft cell in multiple variations: as solid surfaces in exhibition halls, as translucent membranes for interior partitions, as transparent glass on daylighting surfaces, or as bare frameworks displayed as installations. This is akin to the experience of peering into the microscopic world — seeing inside the very cell itself. Across the diversity of the natural sciences, there is a common denominator when, under the microscope or in a figurative sense, we open up the object of our observation.